HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

CHOP's NoT Bleeding Program Advancing Therapies for Hemophilia A and B

CHOP's Novel Therapeutics for Bleeding Disorders (NoT Bleeding) Frontier Program is focused on conducting clinical trials and developing the next generation of therapeutics for hemophilia A, B, and other bleeding disorders.

ingenol [at] chop.edu (By Lauren Ingeno)

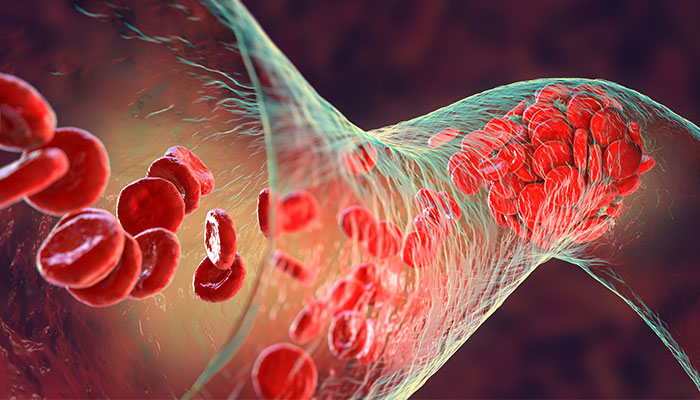

Patients with hemophilia carry a lifelong burden, knowing a life-threatening event could happen at any time without warning. To avoid internal bleeding, patients must inject themselves through a vein, sometimes multiple times per week, with a refrigerated vial of blood clotting factor. Every workout, vacation, and social gathering becomes a calculated risk.

But researchers are rapidly developing new treatments — including gene therapies — that could change all of that.

"Everything these patients do, they're often thinking about their hemophilia," said Benjamin Samelson-Jones, MD, PhD, an attending physician in the Division of Hematology at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "If they're able to get effective gene therapy, that burden is totally lifted."

Dr. Samelson-Jones is one of six researchers who are part of CHOP's Novel Therapeutics for Bleeding Disorders (NoT Bleeding) Frontier Program focused on conducting clinical trials and developing the next generation of therapeutics for hemophilia A, B, and other bleeding disorders.

Lindsey George, MD

CHOP has been at the forefront of developing gene therapies to treat hemophilia for more than two decades. Lindsey George, MD, is an attending physician in the Division of Hematology, leader of the NoT Bleeding Program, and director of the Clinical In Vivo Gene Therapy group. She led the first gene therapy clinical trial to successfully achieve normal or near-normal factor IX activity for adult patients with hemophilia B. In 2017, Dr. George and colleagues were the first to report in the New England Journal of Medicine, that the treatment "nearly universally eliminated" the need for infusions of clotting factor.

That therapy is awaiting approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to go to market. It would be the second one-time gene therapy approved by the FDA for some adults with hemophilia B, following the approval of etranacogene dezaparvovec-drlb (Hemgenix®, CSL Behring) in 2022.

The strength of the NoT Bleeding Program, Dr. George said, is in the bringing together of clinicians and scientists to not only develop new therapies, but also to gain a deep scientific understanding of those therapies, who they will work best for, and how they may interact with other existing treatments.

The NoT Bleeding research team also includes Rodney Camire, PhD, who holds the endowed chair in Hematology Research; Leslie Raffini, MD, MSCE, medical director of CHOP's Hemostasis and Thrombosis Center; Bhavya Doshi, MD, a physician-scientist with expertise in bleeding and clotting disorders; and Hilary Whitworth, MD, MSCE, an attending hematologist.

"We wanted to leverage CHOP's deep bench of expertise in coagulation and gene therapy with this current revolution in new therapies for treating hemophilia," Dr. George said.

Treatment Breakthroughs

Hemophilia is a rare, inherited disorder in which a person's blood does not properly clot. This can lead to internal bleeding, swelling, and bruising. In hemophilia A patients, the dysfunction is caused by low levels of a clotting protein called factor VIII, while hemophilia B patients are deficient in factor IX.

"Conceptually, it's very easy to treat; you just give patients back the protein they're missing," Dr. George said.

However, hemophilia care wasn't revolutionized until the 1980s, when factors VIII and IX became available in freeze-dried powdered concentrates. Since it could be stored at home, patients could self-administer the treatment and skip regular trips to the hospital. By 1995, a prophylaxis treatment became widely available, but it still required patients to inject themselves multiple times per week from infancy through adulthood.

"The problem is, no matter how much factor you give, it's not the same as having a functional version of that protein all the time; you give the protein, and it washes out of your system," Dr. George said. "It's both hard to manage, and it's incompletely effective."

A breakthrough came in the 1990s when, under the leadership of Katherine High, MD, CHOP researchers were the first to test whether they could use a modified virus to introduce a copy of the gene that encodes for the clotting factor that is missing in hemophilia B patients, advancing the theoretic possibility that a one-time gene therapy could cure the disease.

While gene therapy has the potential to transform hemophilia care, challenges persist. Etranacogene dezaparvovec-drlb is currently only approved for patients who are over age 18. This same challenge is present for hemophilia A gene therapy, as well as additional concerns. Namely, gene therapies for hemophilia A have not been able to achieve the same sustained nearly normal factor levels as have been achieved for hemophilia B.

As part of the NoT Bleeding Frontier Program, Dr. George's Lab is working on a second-generation approach to overcome those complications and develop a viable gene therapy for hemophilia A patients.

"What we've observed is that the expression of the factor VIII protein declines remarkably over time," Dr. George said. "We've developed an approach that we are optimistic will provide first-in-class therapeutic benefit. Proof-of-concept basic and translational studies thus far support our optimism, but clinical trial evaluation is ultimately needed to ensure our data carry forward to help hemophilia A patients."

Repurposing a Game-Changing Drug for New Patients

A medication called emicizumab-kxwh (Hemlibra®, Genentech), approved in 2017, has been a game-changer for both adults and children who have hemophilia A. Researchers at CHOP are trying to replicate that success for patients with hemophilia B by repurposing the medication.

Emicizumab is a prophylaxis treatment that works by binding to the activated factor IX and factor X proteins, mimicking the coagulation function of missing factor VIII in hemophilia A. However, since the antibody lasts much longer in the body than factor VIII, patients only need injections twice per month, rather than multiple times per week. Plus, the injections can be given through the skin (like insulin), rather than directly into a vein.

"The burden of treatment is dramatically decreased, and it has the same or maybe even a little bit better hemostatic protection compared to the standard factor replacement treatment," Dr. Samelson-Jones said. "More than 90% of our severe hemophilia A patients are getting it."

Benjamin J. Samelson-Jones, MD, PhD

Dr. Samelson-Jones, who is both a biochemist and hematologist, had a novel idea when presented with a complicated hemophilia B clinical case. He observed that the patient had a specific variant of factor IX with a unique amino acid substitution. Dr. Samelson-Jones hypothesized that emicizumab could reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in this patient and other hemophilia B patients who shared his or similar factor IX mutation.

Now, as part of the NoT Bleeding Program, Dr. Samelson-Jones' Lab is defining the full scope of which factor IX mutations could be amenable to this treatment. So far, they've screened 111 mutations and found that 41 of them could benefit from the medication.

"There are a lot of advantages when it comes to treating hemophilia B patients with this popular hemophilia A drug. We already have so much safety data, including for infants," he said. "My hope is that by repurposing this class of drugs to include patients with hemophilia B, we can provide them a convenient and safe, efficacious treatment during childhood."

In another research aim of the NoT Bleeding Program, Dr. Camire is studying a novel factor V molecule to treat patients who have any factor deficiency. The antibody treatment also could be used for a number of bleeding disorders.

"All of our different approaches are really complementary," Dr. Samelson-Jones said, "so in five years, we'll be able to offer all of our bleeding disorder patients, ideally, multiple good treatment options."