HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

Mini-Intestines: CHOP Researchers Use Lab-Grown Organoids to Study, Treat IBD

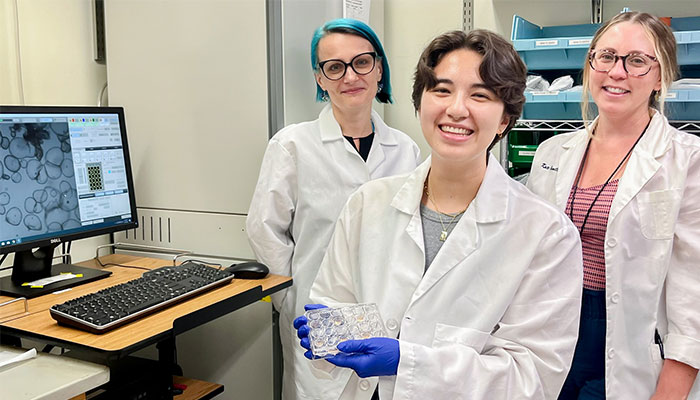

(From left) Tatiana Karakasheva, PhD, Olivia Hix, PhD student, and Kathryn Hamilton, PhD

Stem cells in the intestine's inner lining are responsible for the gut's extraordinary ability to consistently regenerate. Researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia are leveraging that phenomenon to grow and study "organoids" — or so-called "mini-intestines" —to better understand inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

"You can take stem cells from anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, supply them with the right nutrients, and they will start to grow into a three-dimensional structure. The technology has revolutionized the field of cell physiology," said Kathryn E. Hamilton, PhD, an assistant professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania.

As co-director of the Gastrointestinal Epithelium Modeling (GEM) Program at CHOP, Dr. Hamilton creates and studies two kinds of organoids, which are designed to resemble miniature versions of human tissue: Enteroids are derived from a patient's small intestine, and colonoids are derived from a patient's colon. The mini-intestines created in the Hamilton Lab are about the width of a poppy seed and can be seen with the human eye.

Dr. Hamilton and her colleagues are using organoids to investigate the role of stem cells in the epithelial lining of the gastrointestinal tract — as both a driver and potential treatment for IBD. Her lab's three areas of focus are defining unknown intestinal molecular mechanisms, disease modeling, and comparing healthy vs. diseased stem cells.

Treating Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis

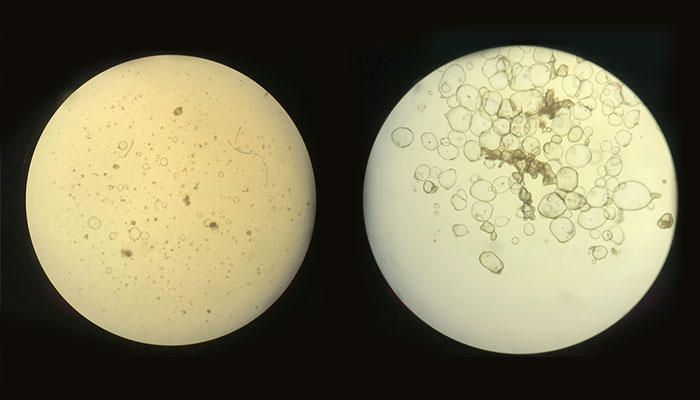

(Left) A microscopic view of organoids derived from an adult patient with Crohn’s disease; (right) organoids derived from a pediatric patient without Crohn’s disease. (Photo Credit: Olivia Hix)

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are the two major types of IBD, characterized by chronic inflammation within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Ulcerative colitis affects only the large intestine, while Crohn's can occur anywhere in the gut. A diagnosis of Crohn's or ulcerative colitis is a lifelong battle. IBD leads to mucosal wounds within the GI tract, which sets off a hyperactive immune response and causes further inflammation. Due to this chronic inflammation, patients can experience severe, debilitating abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, fatigue, and anemia. They often require life-long treatments and may undergo multiple surgeries.

Currently, the only treatments available to treat IBD are drugs that target inflammation.

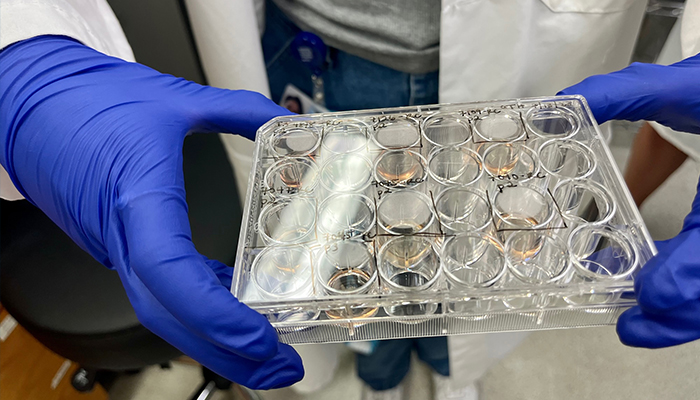

To create organoids, stem cells isolated from endoscopic biopsies are embedded in a three-dimensional matrix and provided with growth factors that mimic the intestine’s environment. (Photo Credit: Lauren Ingeno)

"The major therapeutic strategy is to take the immune response back down to baseline, and let the wound heal itself," Dr. Hamilton said. "The problem is that sometimes the patient's lining doesn't heal itself, and we think that's because there is a problem with stem cells."

Recently, a research team led by Dr. Hamilton compared tissue from healthy patients to enteroid and colonoid cultures grown from pediatric patients with Crohn's disease. The findings were published in Gastro Hep Advances in June. The researchers were interested in finding out whether the colonoids could accurately depict disease-related signals.

Using an algorithm that determined a "prediction score," the researchers' findings validated enteroids and colonoids as valuable models for studying the intestinal lining of patients with IBD.

The research team also wanted to find out if their patient-derived mini-intestines could accurately predict whether a patient had disease in their upper intestinal tract by looking at tissue lower down, in the rectum. This was an important question to answer, because when a patient isn't having a flare-up, their lower intestine often appears "normal," and a diagnosis could be missed during certain testing procedures. Colonoscopies, which are able to more accurately diagnose patients, are invasive.

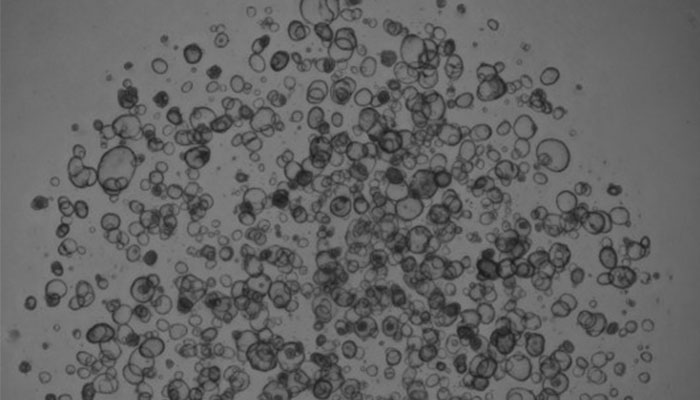

A microscopic view of organoids derived from an adult patient without Crohn’s disease. It is important to study non-disease organoids compared to disease, in order to define what is different, and potentially fixable, in diseased stem cells, Dr. Hamilton says. (Photo Credit: Olivia Hix)

Their study findings suggest that artificial mini-intestines could be used as a noninvasive diagnostic tool to screen for IBD.

"If we could tell by just looking at the piece of tissue at the very end of your colon that you're sick in your small intestine, that would be helpful for diagnosis," Dr. Hamilton said.

Funding from CHOP Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health supported the study, and Tatiana Karakasheva, PhD, associate director of the GEM Program, served as first author.

When it comes to using organoids as a treatment option for IBD patients, Dr. Hamilton said there are companies in Japan and South Korea that are extracting stem cells from healthy areas of the intestine, growing organoids, and then re-inserting them back into the gut with a colonoscope to find and "patch up" the damaged tissue.

One challenge with this technology is finding a way to embed the stem cells back into the intestine without them falling back out. In Dr. Hamilton's Lab, she and her colleagues have begun working with bioengineers at other institutions across the country to use a different gel matrix to help the colonoids "stick to the area of damaged gut long enough to start to grow and make new, healthy intestine."

The project is one of many at CHOP that is leveraging the potential of organoids to treat gastrointestinal disease. As Dr. Hamilton scales up the GEM Program with co-director Amanda Muir, MD, they are collaborating with CHOP researchers who are experts in celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis, Hirschsprung disease, and more.