HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

Study Design

Preliminary Planning

Many clinicians have sparse training in clinical research and they also lack access to a statistician or a research methodologist. Before embarking on a clinical research study, the prospective investigator should avail themselves of educational resources to ensure that their study follows accepted epidemiological principles. This page provides some basic resources to help investigators get started. The federal regulations preclude approval of research whose methodology is so flawed that it won't be able achieve the proposed study objectives.

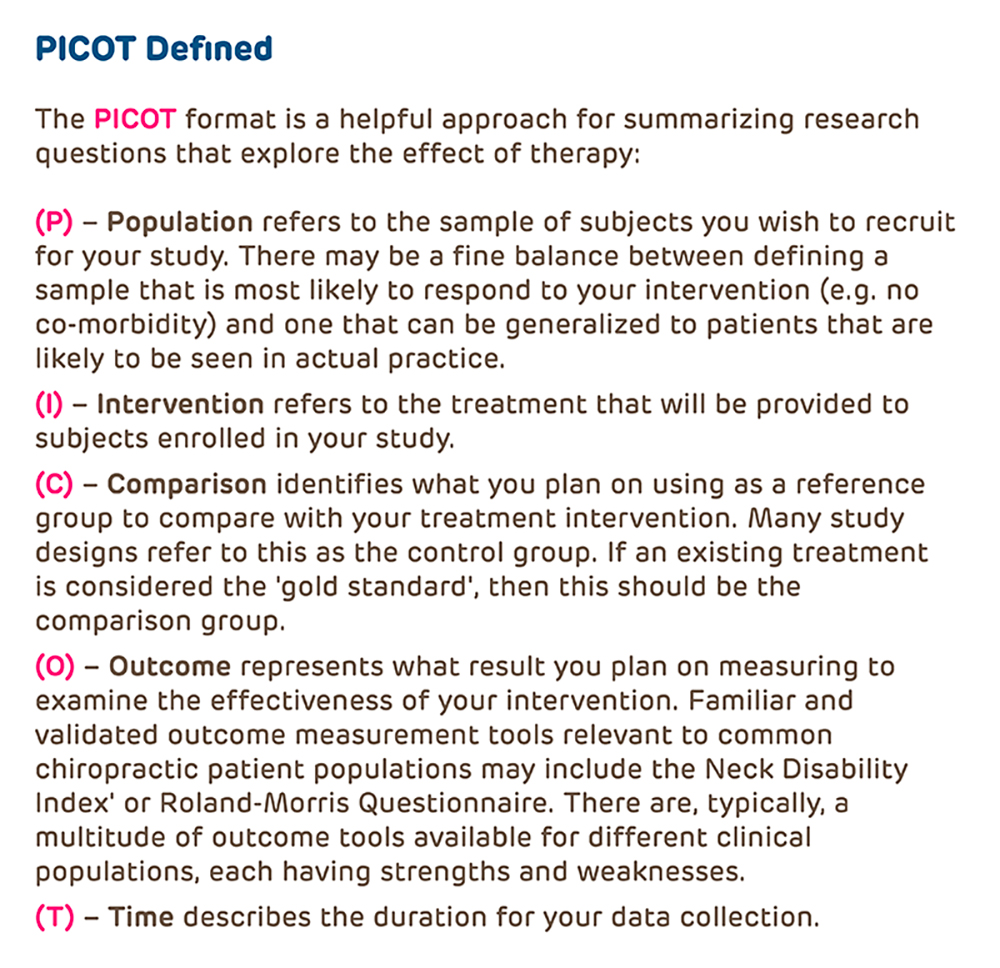

The first step is to develop a research question that is worth answering. The research study question should be framed in a useful format such as PICOT; which is one of several aids used to formulate a research question.

- Population

- Intervention (or for observational studies, the procedures for measurement)

- Comparison(s)

- Outcome measures

- Time

For more information about developing a research question and putting into PICOT format, see the following:

- Haynes RB: Forming research questions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Sep;59(9):881-6

- The concept of PICO or PICOT originated in an editorial published in the ACP Journal Club in 1995. Richardson WS, et al. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club 1995; 123: A12-13.

From Riva JJ, et al. J Can Chiropr Assoc 2012; 56(3)

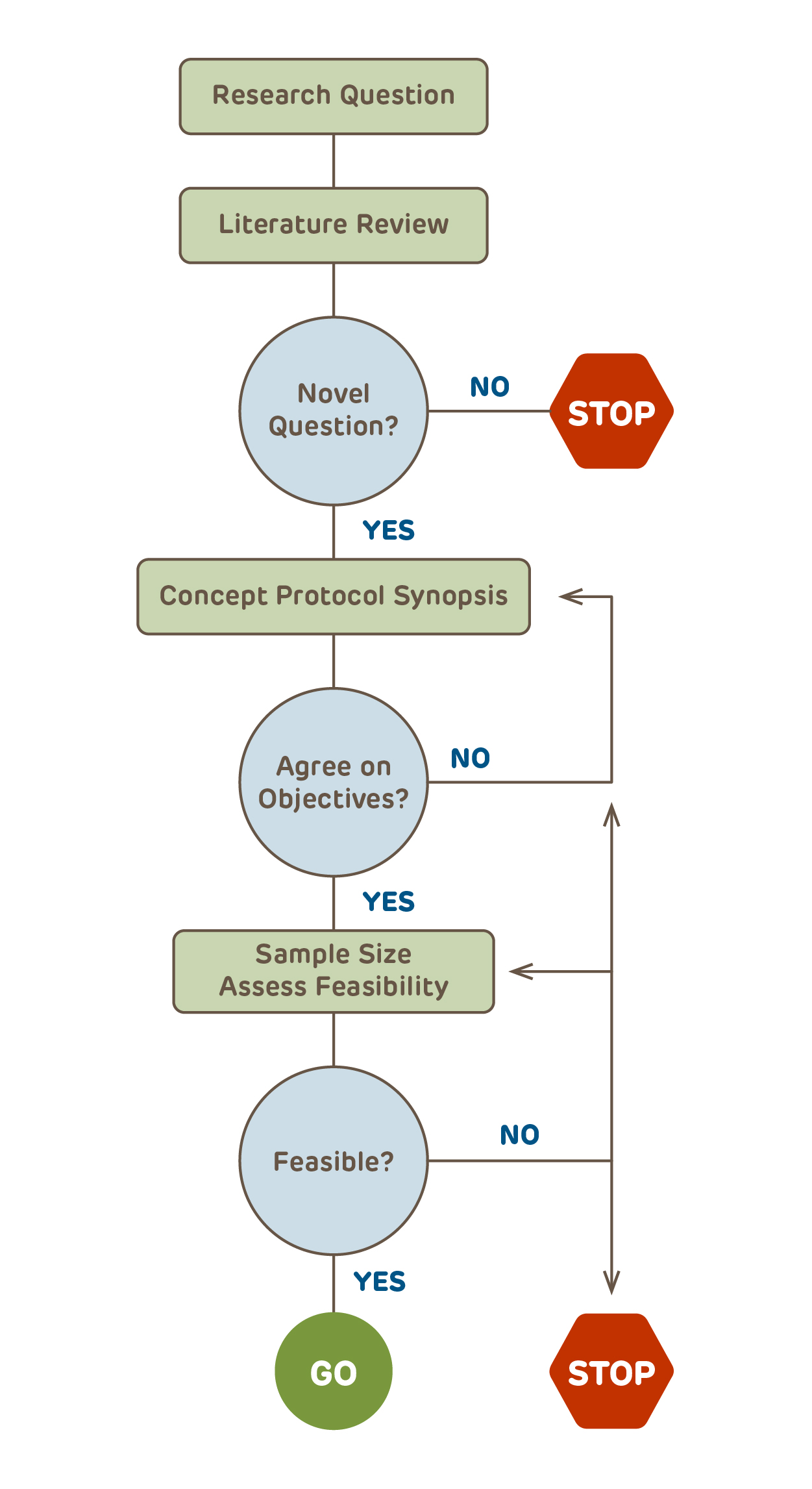

After the Research Question is Defined: Next Steps

With the research question identified, the next step for any study that goes beyond being purely descriptive is to identify collaborators including a statistician or someone knowledgeable about statistics to assist with the study design and planning. Failure to have adequate statistical input at the outset is amongst the most common reasons for studies being deferred rather than approved.

Before the details are finalized, it is best to create a 3 - 5 page high-level concept protocol or synopsis that includes the key design elements (click the link to download a concept protocol template). The synopsis and ultimately the final protocol, need to follow the basic precepts for the type of research design that is chosen. While it may seem an obvious step, the majority of protocols submitted to the IRB do not have a succinct summary of the research design.

After all collaborators have agreed on the concept protocol, the feasibility of the resulting study needs to be assessed. Over half of all studies fail to meet their enrollment timelines. Are there enough potential subjects? Will additional sites be required? Is there funding for the scope of the study? Only after the feasibility of the study is assured should the details of the protocol be finalized. The final protocol should provide sufficient information so that the scientific reviewers, the DSMB (if applicable), the IRB, and ultimately the target journals where the study hopes to be published all have the information that they will need to assess the research.

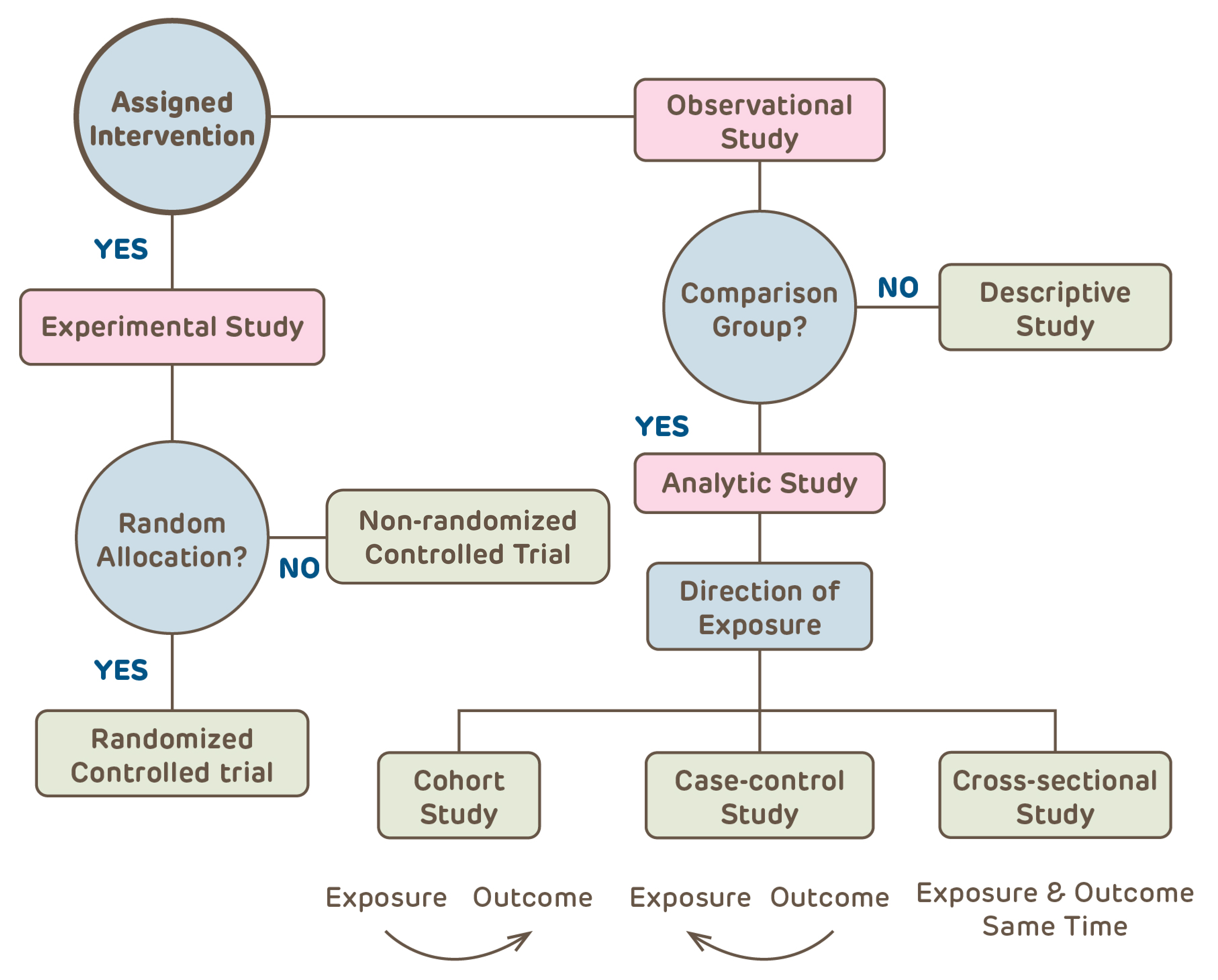

Choose the Right Study Design

Clinical research can be categorized into one of a few basic clinical study designs. Additional specificity may pertain, such as economic analysis, ethnography, focus groups, etc. The archived webpage of the 1993 version of OHRP's IRB Guidebook has a nice overview of clinical research design written for the audience of IRB members.

- Will there be a study intervention (e.g., a drug, a diet or an educational strategy)?

- If YES, this is a Clinical Trial, which could be randomized or non-randomized and have historical, active, concurrent or no control subjects.

- If NO, this is an Observational study

- Is there an analytic plan with comparisons?

- If NO, this is a Descriptive study with no comparisons between groups and an analytic plan limited to summary statistics (e.g., study of natural history of disease, summary of experience with treating a condition).

- If YES, will subjects be followed over time?

- In a Cohort study, subjects are followed from identification of a risk factor forward in time;

- Case-Control studies identify subjects with outcomes of interest and look backwards for risk factors;

- Cross-Sectional studies observe subjects at a single moment in time (e.g., on a single day, at a fixed time, at a single clinic visit)

Note: All observational studies can be either retrospective, prospective or a combination.

The study design affects the types of questions that can be asked, the type of data gathered, the appropriate approach to analysis of the data and the kinds of conclusions that can be drawn from the study. It also impacts the risks associated with the research activity. All of these issues and many more need to be specified in the protocol. Conducting a research study without first defining the basic structure of the study design is like driving a car in a new city without a map (or GPS).

-

Sound Scientific Design and IRB Approval

As a Requirement for Approval the IRB must find that the study minimizes risk through use of sound scientific design. Also, Good Clinical Practice standards require the IRB to assess whether or not the researcher is capable. A poorly written protocol makes it impossible for the IRB to make either of these determinations. It may be useful to examine the Scientific Review Form used by the Scientific Review Committees to see the criteria that they will apply when reviewing and approving protocols.

-

Badly Done Research

Badly done research negatively impacts on medical practice and decision-making, wastes resources and exposes research participants to risks (even if only minimal) without any prospect for benefit to individuals or to science/society.

- The Scandal of Poor Medical Research: We need less research, better research and research done for the right reasons

- The Scandal of Poor Epidemiological Research

- The Continuing Unethical Conduct of Underpowered Clinical Trials (if it isn't scientifically sound, it isn't ethical)

- Why most published research findings are false (one of the most cited scientific articles)

- Why most discovered true associations are inflated (why small studies inflate even true associations)

- Bad Science and the Role of Institutional Review Boards

-

The most frequent reason for delay in IRB approval, particularly for investigator-initiated research, is a poorly designed study. A poorly designed study is not only unethical, it also wastes resources - time, money, educational opportunity - and undermines CHOP's research mission.

- Scientifically unsound research including under-powered studies, can not achieve their stated objectives and are therefore unethical to conduct.

- Participating in a poorly designed study is an inappropriate experience for trainees learning to conduct research.

- A badly designed study will ultimately occupy substantially more of the IRB's time and reviewer effort than a well-designed, carefully planned study.

- Poorly designed research clogs up the IRB Office and delays IRB action on other studies;

- Attention to the basic study design and adherence to accepted clinical research design standards speeds IRB approval and results in valid, useful research results.

Basic Resources for Clinical Investigators

There are many textbooks, journal articles and online resources that discuss clinical epidemiology and biostatistics. The resources include basic sources that the CHOP IRB has found useful as an introduction to the field of clinical research.

Designing Clinical Research: An Epidemiologic Approach

SB Hulley, SR Cummings, WS Browner, DG Grady, TB Newman

An excellent introduction to clinical research, epidemiology and study design. The authors cover observational studies, clinical trials, diagnostic studies and include chapters on basic statistics, data management, research ethics and overall study management.

Clinical Epidemiology: How to Do Clinical Practice Research

RB Haynes, DL Sackett, GH Guyatt, P Tugwell

A fabulous resource written by the MacMaster group. This is a follow-up to their first two texts which focused on understanding epidemiology from the perspective of the clinician and as the basis for evidence-based practice. The focus of this book is on clinical trials but this text should be of interest to anyone conducting clinical research.

Fundamentals of Clinical Trials

LM Friedman, CD Furberg, DL DeMets

This is a small, readable text devoted to the planning, conduct and analysis of clinical trials. A great place to start for those planning on getting started as a clinical trialist.

A consensus statement on writing clinical trial protocols (SPIRIT) and for reporting of study results - e.g. clinical trials (CONSORT), observational studies (STROBE) and diagnostic tests (STARD) - have been developed. More information can be found at the websites below. Adherence to these guidelines helps ensure that all critical elements for conducting and reporting of clinical research studies are included in the study protocol. Journal references for each are included in the next section.

- SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials

- SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials

- CONSORT Statement (Clinical Trials)

- CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated Guidelines for Parallel Group Clinical Trials

- Good ReseArch for Comparative Effectiveness (GRACE Principles)

- GRACE Principles Checklist for observational comparative effectiveness research

- STROBE Statement (Observational Studies)

- STARD 2015 (Diagnostic Studies, updated)

- Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD Statement

- TRIPOD: Explanation and Elaboration

Basic introductory references are included below from introductory series and consensus statements for the reporting of clinical trials, observational studies and diagnostic studies. If the protocol does not contain all of the information that will be required for reporting results, then the quality and validity of the research is suspect.

Overview

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: the lay of the land. Lancet. 2002;359:57-61.

Observational Studies

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Bias and causal associations in observational research. Lancet. 2002;359:248-252.

- Mann CJ. Observational research methods. Research design II: cohort, cross sectional, and case-control studies. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:54-60.

Descriptive Studies

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Descriptive studies: what they can and cannot do. Lancet. 2002;359:145-149.

- Vandenbroucke JP. In defense of case reports and case series. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:330-334.

Database Research

- Haider AH, Bilimoria KY, Kibbe MR: A Checklist to Elevate the Science of Surgical Database Research. JAMA Surgery. April 4, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0628

- Kaji AH, Rademaker AW, Hyslop, T: Tips for Analyzing Large Data Sets From the JAMA Surgery Statistical Editors. JAMA Surgery, April 4, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0647

Cohort Studies

- Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Cohort studies: marching towards outcomes. Lancet. 2002;359:341-345.

- Rochon PA, Gurwitz JH, Sykora K, et al. Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 1. Role and design. BMJ. 2005;330:895-897.

- Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, et al. Reader's guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005;330:960-962.

- Normand SL, Sykora K, Li P, Mamdani M, Rochon PA, Anderson GM. Readers guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 3. Analytical strategies to reduce confounding. BMJ. 2005;330:1021-1023.

Case-Control Studies

Reporting Guidelines for Observational Studies

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573-577.

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:W163-W194.

Clinical Trials

- Kendall JM. Designing a research project: randomised controlled trials and their principles. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:164-168.

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. Lancet. 2002;359:696-700.

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Allocation concealment in randomised trials: defending against deciphering. Lancet. 2002;359:614-618.

- Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Generation of allocation sequences in randomised trials: chance, not choice. Lancet. 2002;359:515-519.

- Perera R and colleagues. A graphical method for depicting randomised trials of complex interventions. BMJ 2007; 334:127-9

- CEBM (Center for Evidence Based Medicine) includes web-based access to the PaT Plot tool described by Perea et al. for generating graphical representations of complex clinical trials.

Reporting Guidelines for Clinical Trials

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, CONSORT GROUP (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:657-662.

- Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al. The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:663-694.

- Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, CONSORT Group. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295-309.

- Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, CONSORT Group. Methods and processes of the CONSORT Group: example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:W60-W66.

Diagnostic Tests

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests. 1: sensitivity and specificity. BMJ. 1994;308:1552.

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 2: predictive values. BMJ. 1994;309:102.

- Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests 3: receiver operating characteristic plots. BMJ. 1994;309:188.

- Deeks, JJ, Altman DG. Diagnostic tests 4: likelihood ratios. BMJ. 1994;309:188.

Reporting Guidelines for Diagnostic Studies