HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

Seeing the Bigger Picture: Modern Imaging Benefits Neonatal Lymphatic Disorders

Modern imaging techniques are improving how clinicians diagnose and treat neonatal lymphatic disorders like central lymphatic flow disorder and chylothorax.

limjr [at] chop.edu (By Jillian Rose Lim)

A picture is worth a thousand words, and with the help of novel imaging methods developed by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researchers, clinicians now have a clearer picture of the lymphatic system at work — an innovation that has led to improved outcomes for infants with severe neonatal lymphatic disorders.

Researchers in the Jill and Mark Fishman Center for Lymphatic Disorders described the impact of these modern, minimally-invasive imaging methods on two complex neonatal lymphatic disorders: neonatal chylothorax (NCTx) and central lymphatic flow disorder (CLFD) in a recent Journal of Perinatology paper. With high mortality and morbidity rates, detecting and diagnosing these disorders early is critical in order to direct the best treatment strategies.

“NCTx and CLFD have been historically challenging to diagnose because there really wasn’t a way to image the system,” said Erin Pinto, MSN, RN, CCRN, first author of the paper and a nurse practitioner in the Center for Lymphatic Disorders. “We really didn’t know the extent of the lymphatic abnormalities without seeing this dynamic contrast through imaging. But here at CHOP, Yoav Dori, MD, PhD, developed a method of accessing different compartments of the lymphatic system where we are able to get a bigger picture of what these kids’ whole lymphatic system looks like.”

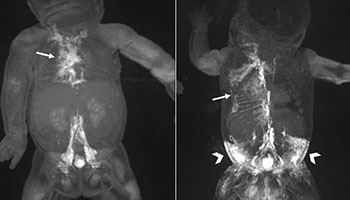

That imaging technology, called dynamic contrast MR lymphangiography (DCMRL), pioneered by Dr. Dori, director of Pediatric Lymphatic Imaging and Interventions and Lymphatic Research, “maps” the anatomy of a patient’s lymphatic system and provide a clearer image of its flow.

“I suspect that as we continue to look, we’re going to find that the lymphatics are playing a role in all kinds of things and all kinds of diseases,” Dr. Dori said. “The lymph system is an organ system and that’s how it needs to be treated. And as with any organ system, you need a tool to do the diagnostics. So we’ve now gotten to a point that we have the capability to do certain diagnostics, but there is a lot of diagnostics that we still need to develop.”

To grasp how DCMRL has improved outcomes in NCTx and CLFD, it helps to first understand how the lymphatic system works — and the challenges scientists historically have faced when it comes to approaching lymphatic disorders.

Seeing the Lymphatic System

A major part of the immune system, the lymphatic system works like a mass transit system carrying its passengers, known as lymph (fluid containing white blood cells drained from tissues) via routes, or vessels, that flow upward through the body. By transporting lymph back into the circulatory system, the lymphatic system helps the body fight disease and infections by ridding it of toxins and waste. When lymphatic fluid leaks, however, life-threatening conditions can occur. In chylothorax, for example, fluid leaks between the lung and chest wall, resulting in severe cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing.

The lymphatic system has been challenging to study because researchers couldn’t visualize it as a whole. But using DCMRL, clinicians such as Pinto and Dr. Dori can look closely at the multiple compartments of the lymphatic system and detect abnormalities not seen on an X-ray, an ultrasound, or an MRI.

“You wouldn’t do heart surgery without imaging the heart — knowing exactly what its anatomy is, where the problem lies, and then planning your intervention,” Dr. Dori said. “That goes for any kind of surgery and everything we do in medicine. The DCMRL does exactly the same thing. It’s imaging that allows us to find out where all the problems are.”

Pinto adds that DCMRL is especially helpful when looking at central lymphatic flow disorder patients who have fluid accumulation in more than one compartment. Furthermore, a patient could very well have one of multiple versions of neonatal chylothorax: Some infants have NCTx that affects one lung, while others may have it in both lungs.

“If they have a multi-compartment problem, there are lymphatic abnormalities everywhere, so that changes our thinking, and we would then have to be very careful of the kind of interventions we choose,” Dr. Dori said. “The interventions have to be very, very targeted toward the compartment that is experiencing the biggest problem whilst also making sure you’re not affecting the rest of the compartments.”

Putting DCMRL to Work in Neonatal Lymphatic Disorders

In the current study, Pinto and her colleagues indeed found that while the use of DCMRL was advantageous for NCTx (in which lymphatic fluid accumulates in one space), it was also beneficial for CLFD (in which fluid accumulates in multiple compartments of the body). In a retrospective study of 35 newborns with either NCTx or CLFD, they reported that using DCMRL was effective in both diagnosing a lymphatic abnormality and providing a clear picture of the extent of the problem.

In patients with NCTx, intranodal injection of ethiodized oil had a 100 percent success rate as a treatment option. Patients who underwent this treatment after DCMRL left the hospital on average about 14 days after receiving the therapy, suggesting the intervention leads to a shorter length of hospitalization.

Meanwhile, in patients with CLFD, the researchers found DCMRL was important in determining the nature of the lymphatic issue, an insight that led to tailored treatment options that, in some cases, improved survival.

“In the past, before advanced imaging, clinicians conducted more aggressive interventions with poor outcomes,” Dr. Dori said. “This paper shows that we learned from the imaging about how to do this correctly — how to conduct more targeted interventions. The outcomes in the current era have improved significantly for these patients.”

What’s Next? ‘Infinite Potential’ From Lymphatics and Beyond

According to Pinto and Dr. Dori, we can naturally expect to learn even more about how to treat lymphatic disorders from here.

“Speaking from the paper’s perspective, the development of better imaging of the lymphatics, especially for patients, for example, with CLFD, has shown us that there are a lot more lymphatic abnormalities out there,” Pinto said. “And now that we have a good idea of what they look like, trying to develop interventional options, like different types of ventilation methods, for these patients is really something that we’re focusing on.”

Dr. Dori agreed the novel imaging methods offer almost infinite potential. Other diseases such as acute respiratory distress syndrome or inflammatory bowel disease have lymphatic components as well.

“When we started, we used this imaging for a very small number of diseases where there was a clear lymphatic problem — something like a chylothorax, which was clearly lymphatic,” Dr. Dori said. “But now we know that chronic lung disease, which is a huge problem in neonates, is an enormous lymphatic problem. Many of those patients are having lymphatic problems.”

Learn more about research from the Jill and Mark Fishman Center for Lymphatic Disorders, a designated Frontier Program at CHOP.