HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

Research Heroes: Strengthening Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Research - Antonio Rosato

From the time Antonio Rosato was diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) at age 4½, his family was eager for him to participate in a clinical research trial. They wanted to give him access to the latest advances in pharmacological and disease management approaches for DMD, an opportunity that Antonio’s uncle Artie, who was diagnosed with the same neuromuscular disease four decades ago, did not have.

From the time Antonio Rosato was diagnosed with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) at age 4½, his family was eager for him to participate in a clinical research trial. They wanted to give him access to the latest advances in pharmacological and disease management approaches for DMD, an opportunity that Antonio’s uncle Artie, who was diagnosed with the same neuromuscular disease four decades ago, did not have.

Research for DMD has come a long way since then, and novel drug therapeutics are beginning to become available for patients with the progressive disease that causes the muscles in the body to become very weak. A child is usually diagnosed with DMD between the ages of 3 and 5, when he starts having difficulty running and jumping. As symptoms progress, he may lose walking ability and is usually wheelchair-bound by his early teen years.

Ongoing research is helping to find new drug therapies to help build and strengthen DMD muscles, prevent other disease-related complications such scoliosis and heart and breathing problems, and improve the overall quality of life for children with DMD.

DMD is a genetic disorder caused by an absence of dystrophin, which is part of a group of proteins that work together to strengthen muscle fibers. In Antonio’s case, the genetic mutation was inherited, but the disease also can occur due to random spontaneous genetic mutations. The tricky thing with DMD is that, despite progress toward a proven treatment, some research therapies work on specific types of DMD — so one treatment may work on one child, but it will be ineffective in another — while others could be of benefit to all people with Duchenne regardless of where exactly in the genetic code the mutation is located.

DMD is a genetic disorder caused by an absence of dystrophin, which is part of a group of proteins that work together to strengthen muscle fibers. In Antonio’s case, the genetic mutation was inherited, but the disease also can occur due to random spontaneous genetic mutations. The tricky thing with DMD is that, despite progress toward a proven treatment, some research therapies work on specific types of DMD — so one treatment may work on one child, but it will be ineffective in another — while others could be of benefit to all people with Duchenne regardless of where exactly in the genetic code the mutation is located.

Antonio and his family, who live in Sicklerville, N.J., had to wait a few years until he was old enough to be eligible to enroll in a clinical trial that is investigating a new drug strategy for DMD. When they got the phone call inviting them to come to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia to see if he qualified as a study participant, “It felt like we had won the lottery, knowing that he could take part in something that could change the lives of so many people and his too,” said Antonio’s grandmother, Deb Foster.

Foster has had a close connection for many years with CHOP and its medical team, who helped to manage her brother Artie’s DMD throughout his childhood. Artie is now 46 and has been married for 22 years.

“He is without a doubt a miracle and the main reason Antonio wanted to be in the trial,” Foster said.

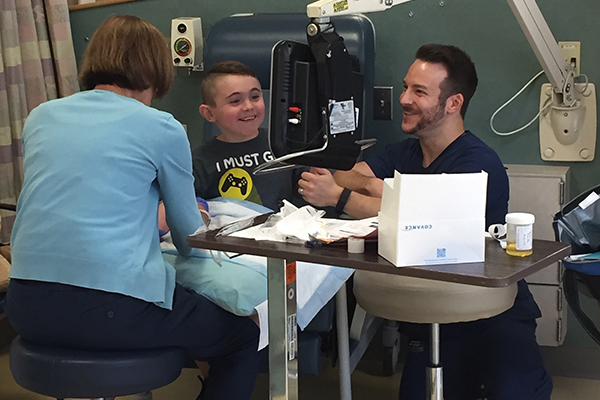

In order to qualify for the trial, Antonio first needed to go through a rigorous day of testing. At one point, Antonio, who had just turned 7 was getting tired and squirmy during a magnetic resonance imaging scan. He got some extra encouragement from Joshua Zigmont, RN, BSN, research nurse coordinator, and the pep talk persuaded Antonio to stay still and calm. They’ve built a trusting friendship, and Antonio now looks forward to coming every month for their lively thumb-wrestling matches that are a good distraction during his bloodwork and drug infusions. Antonio is the reigning champ, but Zigmont is always ready for a rematch and round-by-round commentary of the superfight.

The study that Antonio is participating in is a phase 2 industry-sponsored drug trial. It is placebo controlled and blinded, but it has three randomization groups where patients are either assigned to receiving placebo for one year and then the study drug for one year, vice versa, or assigned to receiving the study drug for both years. Antonio is entering his second year of the clinical trial, and at times it can be frustrating not knowing if and when he is receiving the study drug, Deb said, but they’re always grateful to be part of the research process.

“They’ve given Antonio the opportunity to hopefully experience a better outcome,” Deb said.

She is amazed at how the clinical research staff goes above and beyond to make every experience at CHOP a positive one. Antonio arrived at his latest visit with a warm smile and one of his favorite stuffed animals, Happy, who tagged along for a height and weight check. Vital signs and bloodwork quickly followed. All measurements during the clinical research visit must be recorded in a certain order and at specific times, so Zigmont keeps everything on schedule. But he made sure to squeeze in time for Antonio to have a well-deserved snack, since he was required to fast the previous night.

She is amazed at how the clinical research staff goes above and beyond to make every experience at CHOP a positive one. Antonio arrived at his latest visit with a warm smile and one of his favorite stuffed animals, Happy, who tagged along for a height and weight check. Vital signs and bloodwork quickly followed. All measurements during the clinical research visit must be recorded in a certain order and at specific times, so Zigmont keeps everything on schedule. But he made sure to squeeze in time for Antonio to have a well-deserved snack, since he was required to fast the previous night.

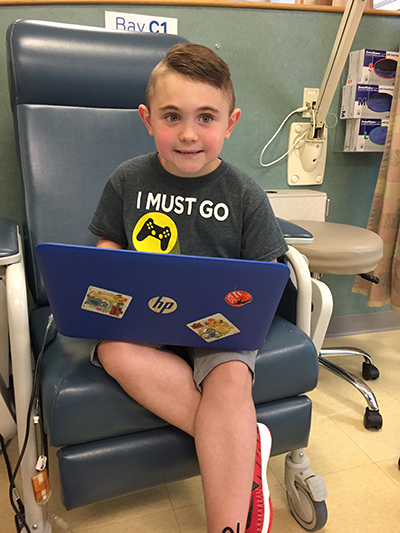

Next, Antonio received his drug transfusion over the course of about an hour, not an easy task for an active little boy who isn’t a fan of sitting still, so TV shows and computer games helped him pass the time. Meanwhile, Foster answered an online survey to assess Antonio’s quality of life and share any family concerns at this point of the study. Antonio was full of questions of his own like, “Where are we going? What’s next? Are well all done?” which Zigmont was always ready for with a jokey answer.

At some visits, Antonio has an appointment with the physical therapy department where CHOP’s physical therapists put a playful spin on tests that measure his muscle strength, coordination, and endurance. They’ll look for a common sign of muscle weakness in DMD, called Gower’s sign, in which a child in a sitting or squatting position grasps his knees with his hands and walks them up toward his thighs and hips to help pull himself upright. Antonio usually wraps up his clinical research day with a magnetic resonance imaging scan and X-rays that also help to show how his muscles, joints, and spine are doing.

At 8-years-old, Antonio obviously is a pro at the clinical research study protocol. Once, he even earned a badge from a CHOP security officer that he proudly showed off in the hospital’s halls. It’s all in a day’s work for this outgoing research hero.