HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

How Peacekeeper Cells Prevent Autoimmune Disease: Q&A with The Oliver Lab

All living organisms, from our complicated multicellular selves to the tiniest entities inside our bodies, have an identity: a set of vital characteristics that guide our daily routines, give us purpose, and unfortunately – even in the case of our microscopic cells – sometimes get lost. In the lab of Paula M. Oliver, PhD, associate professor of Pathology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a group of researchers led by Awo Layman, PhD; Guoping Deng, PhD; and Claire O’Leary, PhD, studied the influential events that transpire when, as Dr. Layman described it to us, a type of immune cell called a regulatory T cell (also known as a Treg cell) suffers a “loss of identity.” Previous research has suggested that Treg cells help protect us from autoimmune disease, but little is known about how their identity is maintained so that they can continue to perform these key roles. We sat down with Drs. Layman and Deng to discuss the fascinating story of their most recent findings, published in Nature Communications, about one key protein that helps Treg cells maintain their character.

All living organisms, from our complicated multicellular selves to the tiniest entities inside our bodies, have an identity: a set of vital characteristics that guide our daily routines, give us purpose, and unfortunately – even in the case of our microscopic cells – sometimes get lost. In the lab of Paula M. Oliver, PhD, associate professor of Pathology at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, a group of researchers led by Awo Layman, PhD; Guoping Deng, PhD; and Claire O’Leary, PhD, studied the influential events that transpire when, as Dr. Layman described it to us, a type of immune cell called a regulatory T cell (also known as a Treg cell) suffers a “loss of identity.” Previous research has suggested that Treg cells help protect us from autoimmune disease, but little is known about how their identity is maintained so that they can continue to perform these key roles. We sat down with Drs. Layman and Deng to discuss the fascinating story of their most recent findings, published in Nature Communications, about one key protein that helps Treg cells maintain their character.

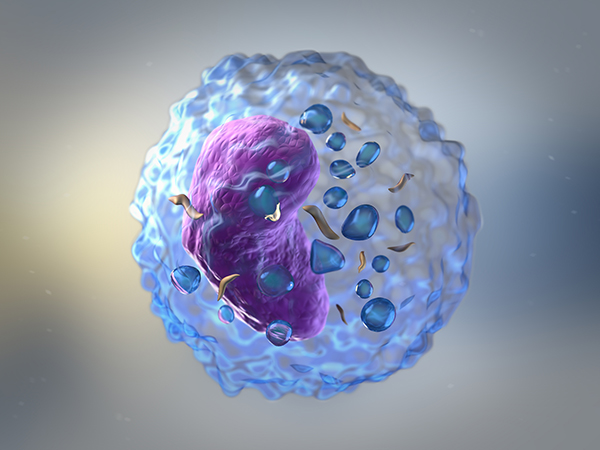

Tell us about Treg cells. What are they, and what role do they play in our bodies?

People don’t usually refer to Treg cells as peacekeepers, but that’s how we like to think of them. They are suppressive cells, and they help keep all of the other cell types in the body quiescent. When we encounter anything that is not part of the self, such as a bacteria or virus, our T cells get activated and make certain proteins (among other things) to help get rid of that invading pathogen. Tregs have a very important role in making sure our T cells don’t misdirect these T cells’ attacks against our own cells. They also make sure that our cells stop responding once the bacteria and viruses have been cleared.

What steps led up to your investigation published in Nature Communications?

Our lab has long studied a protein called Nedd4 family-interacting protein 1, or Ndfip1. We know that Ndfip1 is important for proper T cell function. When we take mice and get rid of Ndfip1 in all cells, the animals start to get sick by six weeks of age. Most of the mice do not survive beyond 12 to 14 weeks of age. So we know this protein helps keep things under control. What we didn’t really understand was whether Treg cells require Ndfip1 to function.

In your most recent study, you continue that investigation. What did you find?

In this study, we generated mice lacking Ndfip1 only in the Treg cells. This means that all the cells in the animals could express Ndfip1 except for the Treg cells. These animals would allow us to understand how the expression of Ndfip1 in Treg cells would affect Treg cell function or identity. We found that starting at about nine weeks of age, the animals started to get really sick. They started to itch and developed severe progressive dermatitis at the bases of their ears. On deeper investigation, we found that their lymph nodes and spleens were quite large. This suggested that Ndfip1 is very important in Treg cells, but what we didn’t know was what exactly it was doing in the these ‘peacekeeper’ cells.

In this study, we generated mice lacking Ndfip1 only in the Treg cells. This means that all the cells in the animals could express Ndfip1 except for the Treg cells. These animals would allow us to understand how the expression of Ndfip1 in Treg cells would affect Treg cell function or identity. We found that starting at about nine weeks of age, the animals started to get really sick. They started to itch and developed severe progressive dermatitis at the bases of their ears. On deeper investigation, we found that their lymph nodes and spleens were quite large. This suggested that Ndfip1 is very important in Treg cells, but what we didn’t know was what exactly it was doing in the these ‘peacekeeper’ cells.

Next, we asked: What changes in protein composition or abundance occur when Ndfip1 is gone? With this data, we tried to establish whether the proteins we identified could point to particular molecular pathways that were altered in the absence of Ndfip1. Our pathway analysis revealed many protein hits associated with metabolism – suggesting that Tregs that lack Ndfip1 are metabolically different.

What impact does this metabolic difference have on the body?

Well, we did an in vitro assay, where we put the Treg cells in a dish and tested their response to glucose. A normal Treg cell doesn’t really like to use glucose as a source of energy because they’d rather use fatty acids. However, when Ndfip1 is absent, Treg cells rely heavily on glucose, and they’re more likely to increase their use of glucose as a metabolic source. Using glucose as an energy source is a behavior often attributed to effector T cells, the cells that actively respond to things like pathogens and viruses. We believe that Ndfip1 helps Treg cells to essentially remember that they’re Tregs by limiting their metabolism so that they don’t become effector cells. Ndfip1 helps Tregs stay true to their identity and fulfill their role of helping to prevent autoimmune disease.

Fascinating! What are some of the practical clinical applications happening with this research?

Well, there are investigators at University of California San Francisco who are investigating the use of Treg cells as therapy in autoimmune conditions like Type 1 diabetes. In type 1 diabetes, the immune system attacks the beta cells in the body that make insulin. Because these beta cells are lost, these patients are not able to make insulin, and so they’re not able to regulate their blood sugar levels. Now we know that Treg cells are important for keeping cells quiescent, so the question is, if we could increase Treg cells in the system, can we quiet down these cells that are attacking beta cells? They call this Treg immunotherapeutics.

Is a loss of Treg identity ever useful?

Well, consider the converse: If we understand the things that help Tregs stay Tregs, then we can also understand things that influence Treg cells to change into other things. In other contexts, like cancer, you actually don’t want Treg cells to be too functional within the tumor environment. Within the tumor, you have immune cells that are trying to attack the cancer, but then you have Treg cells that are keeping these effector cells quiescent when you actually want to promote a very potent immune response. Perhaps someday we can try to understand how we can make cells within the tumor microenvironment not function like Tregs so they’re actually contributing to the fight against tumors rather than suppressing an immune response. That’s less developed, but those are theoretical ideas about how we may be able to use our understanding of how Treg stability is maintained to fight tumors, in addition to their use in fighting autoimmune conditions.