HOW CAN WE HELP YOU? Call 1-800-TRY-CHOP

In This Section

Art From the Heart: Creativity and Cardiac Research Meet

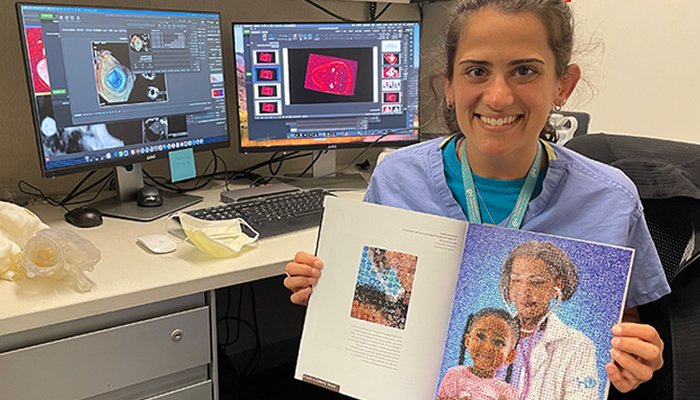

Cianciulli's art was published in Diastole, CHOP's literary and arts magazine.

limjr [at] chop.edu (subject: Art%20From%20the%20Heart) (By Jillian Rose Lim)

Science and art always have been Alana Cianciulli's twin passions, from heart valves to Van Gogh, aortas to acrylic paint. But while these hobbies seem to exist on opposite ends of the spectrum, Cianciulli, a research assistant at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute, discovered a way to bring them together: Working in the lab of Matthew Jolley, MD, assistant professor in the Division of Cardiology, Cianciulli was inspired by 3D images of the heart to create meaningful and masterful artwork.

Cianciulli first joined CHOP in 2019 as a research assistant for J. William Gaynor, MD, and Nancy Burnham, CRNP. While the position fueled her passion for pediatric cardiology, she soon learned of an opening in Dr. Jolley's lab that involved a little bit more artistic flair. Already acquainted with Dr. Jolley and his family (she babysat for the couple's children in her junior year of college), the job was a perfect transition.

"I had two loves — art, then science and medicine — and working with Dr. Jolley was where I was able to blend these passions together," Cianciulli said. "In the lab, we create visual representations of heart models working with patient-specific anatomy, which fuels my creative ability."

Alana Cianciulli

Visualizing the Heart

Researchers in the Jolley Lab focus on visualizing and quantifying abnormal heart structures using multi-modality 3D imaging. Among their many tools is a custom software called SlicerHeart, a publicly available program co-developed by Dr. Jolley and based on the open-source program 3D Slicer.

Through SlicerHeart, researchers can take 3D images such as echo images, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging scans, and build virtual or 3D-printed anatomical models of patients' hearts. The customizable nature of the program is critical, since children with congenital heart disease can have a broad and unique range of anatomy, and few tools are readily available for clinicians to conduct image-based structural phenotyping or patient-specific planning of interventions.

"These virtual models can help outline the workflow of a certain surgical procedure, and the 3D-printed models allow surgeons to see, in the palm of their hands, a patient's heart from a real anatomical perspective before going into surgery," Cianciulli said.

The process of creating these models benefits from an acute eye for the visual and a special spark of creativity. Cianciulli worked specifically on volume rendering in these models, where she takes a CT scan or other image and assigns colors to certain intensities of the heart.

"You're able to get a truly realistic 3D virtual model of these children's anatomies," Cianciulli said. "And if the scan was done in 4D, meaning that there's time associated with it, you can see the heart beating in real time, including the valve leaflets."

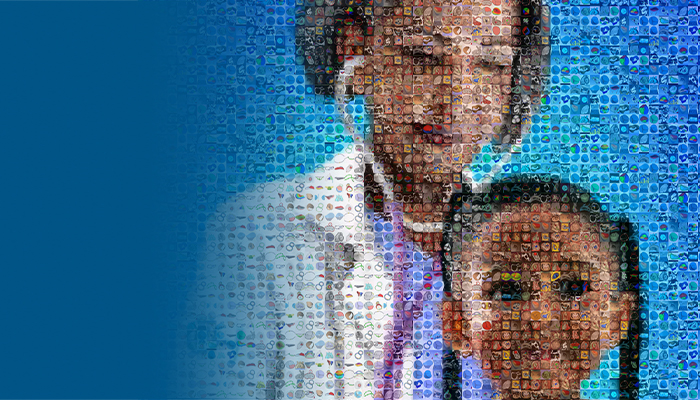

A close-up of Cianciulli's mosaic, made up of SlicerHeart models.

Making a Heart Mosaic

But Cianciulli's creativity at work didn't stop there. Inspired by the models and renderings created in SlicerHeart and with Dr. Jolley's encouragement, she decided to submit an art piece to Diastole, CHOP's literary and arts magazine. Along with a colleague in the lab, she conceived of a mosaic made up of miniscule images of virtual and physical models created by the lab.

"We brainstormed ideas and thought of using these images, scaled down in size, as mosaic pieces that form a physician with a stethoscope, listening to a child's heart," Cianciulli said. "We went through a couple iterations, and I drew the original drawing on my touchscreen tablet."

Following that, she used a program to create the mosaic, which will soon hang in physical form in CHOP's Cardiac Center.

"These images are all mostly manual segmentations that our lab members might have spent hours on, painting one single leaflet and getting that full, complete picture of the heart," Cianciulli said of the mosaic. "If you see a picture with a bigger field of view and it's really colorful, that's volume rendering."

Passion-combining Career

Cianciulli recently started medical school at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine while staying on with CHOP as a consultant. She plans to bring her love of art on her medical career journey. It is, after all, not just a part of her job, but a way to relieve stress and indulge her artistic expression. Even at an early age, Cianciulli would doodle in her notebooks when distracted in school. In college, after taking a painting course, she became hooked on acrylic painting, learning how to blend and match colors.

"I like looking at a subject and translating it to paper," Cianciulli said. "But now that I've gotten better associated skills and have learned proper techniques, I share art with my family and friends. I like painting things for people as presents or just creating little things to show them I'm thinking about them. It's so relaxing, and I think it's also good for me because it has taught me patience. You have to keep working at it, and as you keep going, you see it evolve so quickly. But the more time you spend on it, the better it will be. And you just see those results so clearly with painting."

Cianciulli's favorite art commissions are gifts for those she loves, whether it's a painting of her grandparents, an elephant, or a Van Gogh rendering. As a med student, Cianciulli also hopes to keep focusing on cardiology as a specialty. She encourages people to pursue their passions, even though they don't always fit into the same mold.

"I want to tell people that it's possible to make your passions work together — you might think that some kind of crazy combination will never work out. But I think you can make anything work if you really want to," Cianciulli said. "I feel lucky because Dr. Jolley supported me in this, and many people don't have that opportunity or support. I think the best part of that has been that I can now see myself translating my art into my science and seeing how they can work together nicely. My pre-medical advice is to allow yourself to let your passions come together because there's something really beautiful that can come out of it."